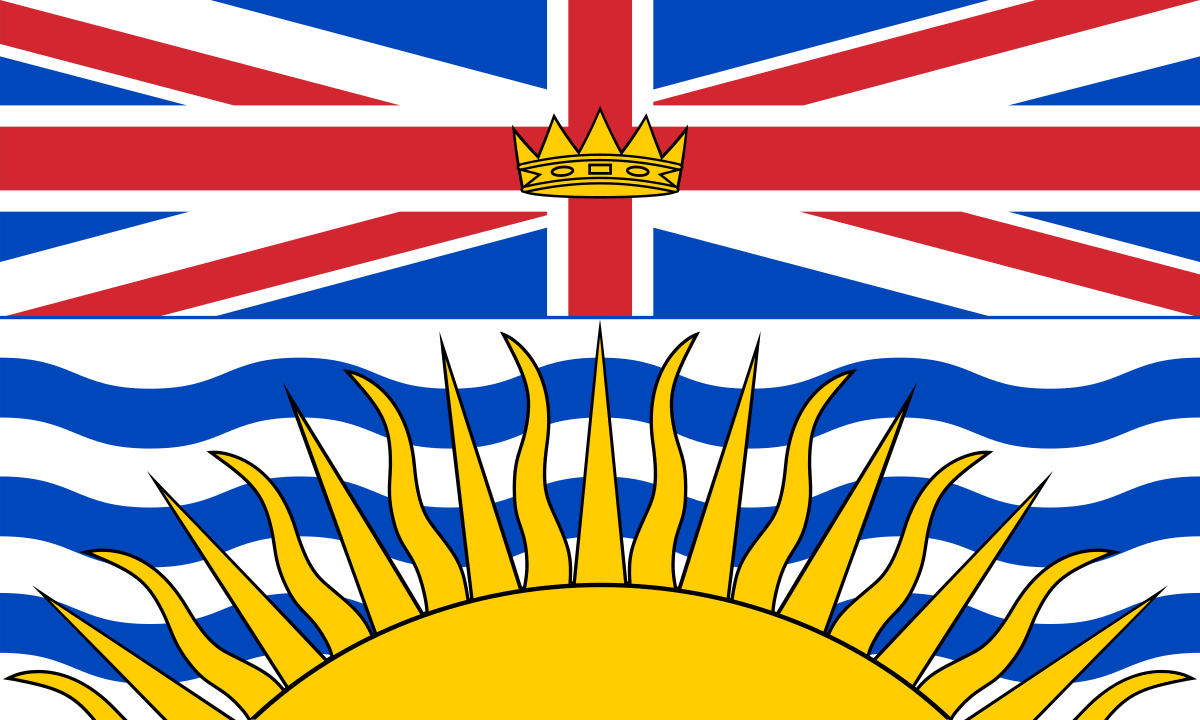

As I write this, I’m getting ready to leave for my seventh season of tree planting. I’ve had an eye on the weather all winter, watching as the snowpack levels in British Columbia reach lows not recorded since at least 1970, watching as rivers — like the confluence of the Nechako and Fraser rivers in Prince George — run dry.

According to data from Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s National Agroclimate Information Service, by the end of March this year 85 per cent of B.C. was considered abnormally dry or in moderate to exceptional drought. The region that I’ll be planting in, near Burns Lake, is one of the driest in the province.

Over the years I’ve had many doubts about the ecological benefits of the province’s reforestation practices.

But last season marked the first time I started to wonder if tree planting might someday become ecologically unviable in some regions of the province.

The lack of precipitation coupled with unseasonably high temperatures made the soil on some blocks so dry and compacted it was like planting into a sheet of rock. I was often struck with the sense that the earth was actively rejecting the trees I was planting. I imagined the trees I’d planted withering and dying, eventually becoming fuel for the wildfires that were then burning all around us.

Was it possible that these intensifying climatic events could render some ecosystems unable to support the growth of new trees? Was I on the frontlines of witnessing the beginning of the end of reforestation as we’ve known it for the last 50 years?

I decided to ask around. I spoke to Sally Enns, who works as a forestry manager contracted by the Cheslatta Carrier Nation and is an incoming supervisor at the reforestation company I work for; we were based out of the same bush camp for part of last season. Reflecting on the drought conditions, she articulated many of the same concerns that I’d had.

It’s not all doom and gloom in the article: * But when Enns did return in the fall, what she saw surprised her. While she hasn’t finished crunching the numbers yet, she says that across all different blocks, mortality rates were much lower than she’d expected: many of the trees had survived.

“I was shocked,” Enns told me. She took photos of the blocks and sent them to her friends and co-workers who’d planted them*.

Absolutely, there’s some good news in amongst the bad.